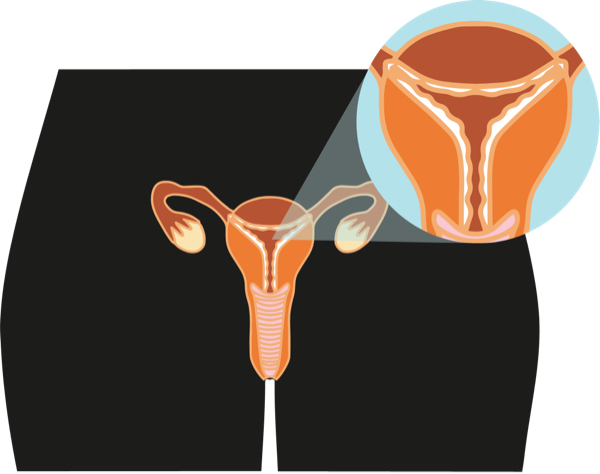

Sometimes when women find out they have endometrial cancer, they may not have had any symptoms and never knew they had a problem.

There are a number of symptoms or changes to look out for, including:

- bleeding from the vagina after menopause

- bleeding from the vagina between periods

- an unusual discharge (ooze) from your vagina, especially if you have been through the menopause. This discharge might be watery, or it might have blood in it or have a bad smell.

- pain in the belly

- pain when you’re having sex

- finding it hard or painful to pee

- losing of weight without trying.

Having these symptoms may not mean you have cancer, but it is important to check. It’s not unusual for some of these changes to happen around the menopause, and it’s usually not due to endometrial cancer.

All women who have vaginal bleeding after they have had the menopause should be referred by their doctor to a gynaecologist, who is a doctor that specialises in women’s health. Ask your doctor, nurse or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander health worker about this. You can request females doctors, nurses and health workers to follow Women’s Business protocols.

If you have any of these problems, or are worried about something else, yarn with your doctor, nurse or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander health worker.